Column Name

Title

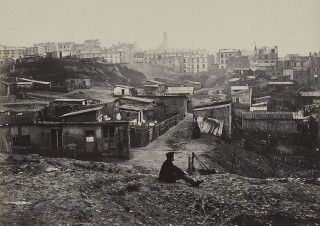

Top of the rue Champlain, View to the Right (20th Arrondissement) (1877–78), albumen silver print from glass negative, 26 x 36.6 cm (Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet)

More Photos »The revelatory and stunning photographic exhibition now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art called Charles Marville Photographer of Paris should not be missed. And its accompanying smaller show, Paris as Muse, which is also well worth seeing (and which is also up through May 4), helps to demonstrate Marville’s influence on several well-known photographers including Atget, Brassaï, Nadar, Steichen, and Stieglitz.

This show and the related Paris as Muse: Photography, 1840s-1930s, are up at the Met through May 4.

Body

Marville (1813-79), despite his enormously large output and longevity, is among the least studied French 19th-century photographers. One reason may be that he changed his last name in 1832, though not ever formally, from Bossu, which means “hunchback” in French, perhaps partly due to the publication of Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame that same year. Whatever the reason for his relative obscurity, it’s still astonishing that the Met show is one of the first to present this under-known artist to the public.

During the 1850s, photography had as its audience an elite few who desired exquisitely crafted prints. But during the 1860s, photographs became more commercially available and thus reached a larger audience. Although this put some early photographers out of business, for Marville, it presented opportunities. Beginning in 1862, he served as the official photographer of the city of Paris and documented the modernization of the city for Emperor Napoleon III (Louis Napoleon) and his chief urban planner, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, during France’s Second Empire (1852-1870). This modernization became known as the Haussmannization of Paris, and in Marville’s photos, we see the development of a city traversed by broad boulevards such as the Champs Elysées, Boulevard des Capucines, and Avenue de l’Opéra.

To get to that shining city, though—one that’s been memorialized by Manet, Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Caillebotte, and pretty much everyone who’s ever been in Paris since—took a lot of work. Starting in the 1850s, workers razed old narrow streets and small houses in order to make room for wide, spacious avenues. They built new bridges and remodeled older ones, in some cases removing houses that lined the bridges. This modernization created more space, and a new look, but the cost was high in that many old structures had to be destroyed. As this radical modernization took place, the renovations also pushed out poor- and working-class Parisians to the suburbs, not merely displacing them, but also squelching their left-wing activities and sympathies.

Being in the employ of the emperor, Marville, if he did have sympathies for the poor, presumably had to keep them hidden. His job was to show the many improvements and the better life promoted by Louis Napoleon’s regime. But the photos in this exhibit show that he did not restrict himself to documenting the new; he also demonstrated a fascination with change itself. By photographing old and new side-by-side without sentimentality, he allows the viewer to regret the loss of old Paris while still welcoming some of the innovations.

Marville’s photographs occupy three galleries at the Met. The show begins with his early career as an illustrator; he only took up photography in 1850. Prior to that, he traveled with painters, some of whom came to be known as the Barbizon School, to the Forest of Fontainebleau. In one of his early photos, Man Reclining Beneath a Chestnut Tree (c. 1853), which captures the brilliance of the sunlight, the man (possibly a self-portrait) nestles against a tree trunk, his fedora artfully placed a short distance away. This Romantic trope of a small figure in nature also appears in many mid-19th-century paintings. Marville also photographed boulders, streams, and waterfalls in the rugged but ragged forest—and his compositions were very much like those of his painter friends including Theodore Rousseau and J.B.C. Corot.

Paradoxically, Marville’s later photos—which have frequently been considered so objective as to serve only as documents—are now considered works of art. Take for example Rue de Constantine (1866). In its beautiful composition, we perceive the rhythm of three lone men receding into the distance, standing beside piles of bricks, shovels, and picks. A few horses and wagons feebly negotiate the torn-up streets. Buildings on each side seem to be watching with their eye-like windows, some shuttered and some partially open. A lonely emptiness in this scene almost looks ahead to paintings of Edvard Munch toward the end of the 19th century—or perhaps even to the metaphysical paintings of Giorgio deChirico in the following one. These were by no means candid photos, but rather ones that the photographer carefully and artfully set up. Indeed, photographic historians have found that Marville posed most of his subjects. (A footnote: at bottom left is a poster advertising American-style retractable umbrellas.)

During the 1860s, the Parisian architect Gabriel Davioud designed and installed public amenities such as gas lamps, benches, fountains, and even urinals. Embellishing the city, they also improved its functionality and hygiene, and Davioud commissioned Marville to document them. A number of the more than 90 photos he took of lampposts plus many of the new “modern” pissoirs—which were strangely but undeniably beautiful with an Art Nouveau feel—are included in the show. (A side note: These still existed when I first lived in Paris, and the mere sight of them evokes in me the stench emanating from them.) Not surprisingly, the most ornate pissoirs were designated for luxurious neighborhoods, such as the one near the Opéra.

Marville loved signs—shop signs, advertisements, and posters plastered to cylindrical kiosks—and he incorporated them into many of his photos. In some ways the proliferation of colored advertisements on these elegant columns became an earmark of Haussmann’s Paris.

Several later photos explicitly document social inequality: the division of Paris into two cities, one rich and one poor. For example, in Top of the Rue Champlain (1877-78), a young man sits atop a desolate hill, looking down at a shantytown stuck in a kind of valley with tall Parisian buildings glistening behind it, beyond the reach of the poor, who are displaced. As in many of his photos, Marville posed the young man, probably an assistant, for the shot. This particular area of the city, noteworthy as a stronghold of the left, remained among Paris’s least developed for decades.

The strength of this show is that it makes anyone who has visited or lived in Paris nostalgic and eager to return, while at the same time posing questions and addressing problems—including some that we still face today.

Everybody will have their favorite subjects, but mine are the gargoyles of Notre Dame abutting an angel, the lampposts, the pissoirs, and the newspaper stands. Ironically, many of these things have not changed much since Marville’s time. The spires of churches, the gargoyles, the bridges, and elegant hotels and boulevards of Paris remain. One can’t help wondering what Marville would have thought of the Tour Montparnasse, constructed from 1969 to 1973, a building so ugly that it is said that the most beautiful view of Paris is from the tower—because that is the only place from which one cannot see it.