Column Name

Title

As if tailor-made for Juilliard, the exhibition at the Jewish Museum titled “Chagall and the Artists of the Russian Jewish Theater, 1919-1949” organically connects theater, music, visual art, costume, film, and documentation. The painter Marc Chagall and the actor-turned-director Solomon Mikhoels are both at its heart; indeed, the exhibition reveals that the prodigiously talented, ill-fated Mikhoels (1890-1948) was actually influenced in his acting technique by the art of Chagall.

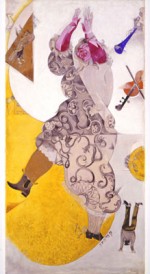

Marc Chagall, Dance (1920); tempera, gouache, and opaque white on canvas; State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow.

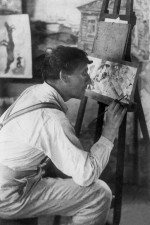

(Photo by © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.)Marc Chagall painting Study for Introduction to the Jewish Theater (1920), photograph, private collection, Paris.

(Photo by © 2008 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.)Natan Altman, Portrait of Mikhoels, 1927 (oil on canvas), A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum, Moscow.

(Photo by © Estate of Natan Altman/RAO, Moscow, via VAGA, New York)Isaak Rabinovich, Shloyme (costume design for Mikhail Shteiman in God of Vengeance) (1921), pencil on paper, A. A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum, Moscow.

(Photo by © A.A. Bakhrushin State Central Theater Museum, Moscow.)Body

The first thing you see upon entering is a 1927 portrait of Mikhoels at the age of 37, painted by Natan Altman (1889-1970). In a powerful, quasi-expressionist portrayal, breathing the same spirit as portraits by the Austrian Expressionists Oskar Kokoschka and Egon Schiele, Altman shows the actor seated on a red chair, gripping one gnarled hand in the other, deep in thought. As Susan Goodman, the show’s curator, explains, it sets the tone for this exhibition.

And the tone continues through a variety of strong and colorful characters, costumes, and sets, but always exposing the suffering underneath. Throughout the visit one hears ambient klezmer music drifting out from video clips. At the same time that you want to tap your feet, even dance, you cannot keep from weeping because of the fate of Mikhoels and his beloved theater; it echoes the trials of the Jewish people as a whole. Laughter and tears: that is the story of oppressed and persecuted peoples everywhere and at all times. It is what Jews and blacks shared in the early to mid-20th century in the United States. It is the blues; it is people who laugh and sing about their own misery, making fun of themselves—and because they do this, they rise above it, performing and weaving works of art.

Great actors, poets, musicians, dancers, entertainers, and artists of all kinds arose from both these origins. The list is long, but among artists who immediately jump to mind are Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, and Count Basie, as well as Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, Stan Getz, and Paul Desmond. Amos and Andy take their place alongside Mrs. Goldberg (Gertrude Berg), and Fanny Brice. It cannot be a coincidence that the television show The Goldbergs, with Gertrude Berg dispensing Jewish humor and wisdom, ran from 1929 to 1955, and Fanny Brice, the comedian, singer, and actress on whom Barbra Streisand’s Funny Girl was based, had her top-rated radio program The Baby Snooks Show from the 1930s to her death in 1951. The radio program Amos and Andy (which, though created by white actors and controversial, was based on real black people) ran from the 1920s through the 1950s.

From at least the time of slavery—and later, the pogroms in Russia—blacks and Jews, like other Diaspora peoples, invented ingenious methods of survival. Indeed, both have created their own music and theater, even constructing distinct languages.

The Jewish Museum show brings to us numerous manifestations of these inventions, focusing on two historic, groundbreaking and unique theater traditions. The first is Habima, the Hebrew-speaking theater (now the National Theater of Israel). Habima’s first director was no less than a protégé of the famed Konstantin Stanislavsky. Unfortunately, most Russian Jews did not speak Hebrew, and Habima departed Russia to go on tour in 1926, never to return. The second, called Goset (Gosudarstvenny Evreysky Teatr, the Yiddish-language Moscow State Yiddish Theater), reached Jews and non-Jews alike. It died soon after the assassination of Mikhoels in 1948. Most productions consisted of original plays based on Jewish folklore, stories by Sholem Aleichem, and those of other famous Jewish writers. But Goset also featured the work of other playwrights, even including a 1935 Yiddish version of Shakespeare’sKing Lear, starring Mikhoels. There is a video excerpt in this show (and I find it fascinating to note that the so-called “Voodoo Macbeth”—an all-black production set in 19th-century Haiti, directed by Orson Welles and Juilliard’s own John Houseman—was produced in New York in 1936 by the W.P.A. Federal Theater Project).

The more than 200 works in the exhibition include drawings and paintings of costumes, maquettes and plans for set designs, a few original costumes, and numerous photos and video clips. Many have never been seen before in the West. I was struck by the extreme modernity of many of these. Natan Altman, a recognized avant-garde artist even before he worked for the Jewish Theater, had also painted Lenin’s portrait and designed the first Soviet postage stamp. His maquette for the set of Uriel Acosta (1922), a classic German drama, is characterized by minimal, geometric, abstract design, very much in keeping with Russian Constructivist design of the time. This is also true of his sets and costumes for other plays, notably The Dybbuk, produced in 1922. Both The Dybbuk and The Golem (1925), designed by Ignaty Nivinsky, used themes from Jewish mysticism, together with contemporary European-flavored expressionism, combined with Cubo-Futurism and science fiction. These robot-like forms and mechanistic elements were the very same ones that arose in Italian Pittura Metafisica, as well as in French, German, Swiss, and American Dada and Surrealism, and in films such as Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times of 1936.

Some of the productions made me smile, while trying to hold back tears. Numbers of comedic plays included characters with names like Schloyme, Yenta, Moishe Pipik, Chaim Yankel, and Schmendrik. I have surveyed some of my friends, who, like myself, were brought up by secular Jews in New York City. Growing up, we all thought our parents and relatives invented these names, but here they are—in the vibrant Jewish theater of the 1920s and ’30s in Russia. These were “our people.” Some came from Sholem Aleichem, author of tales from Chelm, the fictional town passed over and forgotten by the angel who distributed brains. Words like “schlemiel” and “schlemazel” have even entered the American English vocabulary.

The centerpiece of the show is the gallery replicating the original, intimate setting for the Goset Theater; it contains Chagall’s 1920 murals. These were painted in Chagall’s trademark combination Expressionist, Cubist, dreamlike style of the time; they had disappeared in 1937, but were uncovered in 1973. Creating a total environment, they had powerful significance for the artist, and remain among his most poignant works.

The show ends as it begins, with Mikhoels—his murder in January 1948 by Stalin’s henchmen or secret police, an event shrouded in mystery. Ironically, this dedicated artist and fighter against fascism appears to have been targeted as the unofficial leader of Russian Jewry. The photo of his coffin, the case containing his broken eyeglasses, and the film clips of his funeral (attended by more than 10,000 people) are devastating.

The exhibition, which tells the story of the vibrant synthesis of the arts that was unique to the Jewish Theater after the 1917 Russian Revolution, continues at the Jewish Museum (1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street) till March 22, when it travels to San Francisco’s Contemporary Jewish Museum.