Column Name

Title

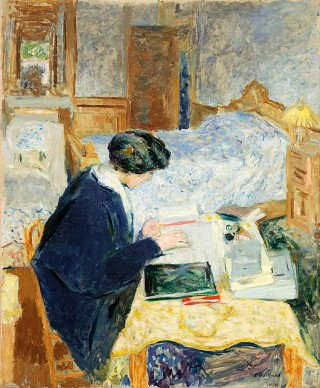

Edouard Vuillard, Lucy Hessel Reading (1913), oil on canvas

(Photo by The Jewish Museum)The extraordinary exhibition “Edouard Vuillard: A Painter and His Muses, 1890-1940” focuses on collectors and patrons and their influence on modern art, and it follows a theme that has run through a number of shows the Jewish Museum has mounted in recent years. Happily, it also affords the opportunity to re-examine some exquisite paintings by Vuillard, one of the greatest under-known artists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. About a quarter of these works have never before been exhibited in the United States.

Body

At first it might seem surprising for the Jewish Museum to feature a non-Jewish painter; however, the show’s thesis makes it clear that the choice is absolutely appropriate. Vuillard’s numerous and powerful Jewish patrons were indispensable to his art and life. But they were not only his supporters, they were also his social circle, his models, and his muses. Among these families were the Natansons, the Kapferers (associated with the Rothschilds), the Bernheims, and the Hessels. These and other wealthy Jewish people (such as the Steins and the Cones, whose roles have been highlighted in previous Jewish Museum exhibitions) played a crucial part in the development of European arts in the early 20th century.

Thadée Natanson, art editor of the symbolist journal La Revue Blanche, and his intriguing wife, Marie-Sophie-Olga-Zenaïde Godebska (Misia for short), occupied a central place in Vuillard’s early career (1895-1900). Misia was a talented pianist who had studied with Gabriel Fauré, and she organized salons that included poets Paul Verlaine, Paul Valéry, and Stéphane Mallarmé; writers André Gide and Colette; composers Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel; and, among other arts luminaries, Enrico Caruso and Sergei Diaghilev. Later on, Misia would be friends with Picasso, Marie Laurencin, Jean Cocteau, and Coco Chanel. One of the many portraits Vuillard made of Misia, a small oil on cardboard dated 1897-99, looks quite similar to works done by Toulouse-Lautrec in the same era.

The wall text accompanying the elegant, almost Renoir-like portrait of Claude Bernheim de Villiers (1905-06), the 3-year-old son of Vuillard’s dealer, struck a chilling note: the finely dressed boy, so representative of the early 20th-century life of luxury of art and art dealers (many of whom were Jewish), was destined to perish in Auschwitz in 1943. Indeed, extremes of fate frame this show. While some Jews, like the Bernheims’ son, were murdered in concentration camps, others succeeded at the highest levels of finance. For example, Henri Kapferer was the founder of Air France; his brother Marcel was an executive in an oil company that became Shell.

There are a range of Vuillard’s early works in the exhibit including the fascinating Self-Portrait With Waroquy (1889), which he did when he was 21, and which reminded me of portraits by Egon Schiele, James Ensor, and others in which death is a doppelgänger. There are also a number of claustrophobic, patterned paintings in bourgeois interiors. Critics most often characterize these in terms of flatness and modernism, but I have always found a darker, more symbolic meaning. In fact, I sense in these an affinity to Munch, Ensor, Schiele, and other northern Europeans. Vuillard allied himself with Pierre Bonnard, Ker Xavier Roussel, Paul Sérusier, Felix Vallotton, Maurice Denis, and others, in a group called the Nabis, the Hebrew word for prophet, a term that has always puzzled me. Some writers have interpreted the term nabi as prophesizing modern art, but I perceive it also as something more all-encompassing, and perhaps more foreboding—that his symbolism anticipated the decline of European civilization that led to the two world wars.

Although I had always tended to prefer Vuillard’s earlier work, I hadn’t seen as much of the later paintings as they have not often been shown. After this exhibit I could see myself acquiring a taste for the later work. Lots of other people certainly did—Vuillard became a highly sought-after portrait painter and decorator after World War I and into the 1920s and ’30s.

The term “decorative” is often pejorative, but in Vuillard’s work, it takes on a new and fresh meaning. Of course, obvious affinities to Japanese art and Art Nouveau run throughout his work.

Twilight at Le Pouliguen (1908) looks ahead to his later murals but is also reminiscent of some of Whistler’s Nocturnes. In fact, Whistler was an early proponent of art for art’s sake, or decorative art. I noticed that many of Vuillard’s interiors with people (he preferred to call them people in their surroundings rather than portraits) resemble those of Whistler. Like Vuillard, Whistler can also be seen as a precursor of modernism and abstraction; he was far more concerned with patterns and shapes than with personalities and psychological studies. Vuillard’s decorative panels for private houses and his posters and graphic illustrations dazzle the eyes.

The artist’s masterful lithographs make up a portion of the show, and it is mentioned that he also painted sets and designed costumes for theater. In fact, the catalog emphasizes that the coming together of the arts of writing, books, poetry, music, and visual arts played a major part, imbuing Vuillard’s life with the theatrical quality of the times.

There are a number of highlights of the exhibit in addition to those already mentioned. In Woman in a Striped Dress (1895), Vuillard’s signature patterns jump out amid lush floral displays and they both contrast with the pallid faces of the women, not unlike those in Degas’s famous Woman With Chrysanthemums (1865), which is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. In Lucy Hessel at the Seashore (c. 1904), the wall text compares Lucy to Venus or a sea nymph; her features are indistinct, and the pastel pinks envelop her as if in a seashell opening out to the sea beyond. This painting is reminiscent of the work of the symbolist Odilon Redon, whose work Vuillard was known to have admired.

Another highlight is Vuillard’s strangely moving and lugubrious last work. Called Garden in Winter With Peacock (c. 1939-40), this large and mysterious painting remained in his studio at his death. The contrast of peacocks and other exotic birds to a bleak landscape might augur tragedy, perhaps reflecting the master’s sensitivity not only to his own declining condition (he died of heart failure in 1940), but also to the ominous state of the world at that time.

I want to emphasize that the main significance of this exhibition does not lie in the beauty of the art, but rather in providing the poignant context. What it succeeds so well in doing is placing a marvelous artist into historical perspective. Without the environment of wealthy Jewish patronage and those patrons’ embrace of modern art—and their horrific destiny—this would have been just another beautiful exhibit. But it goes beyond that; it is transcendent.