Column Name

Title

The current exhibition at the American Museum of Folk Art is an eye-opener. Its title, “Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue and the Carousel,” simultaneously intrigued and puzzled me. What correlation could there possibly be between synagogues and carousels?

Body

To see the show and read a bit about it is to be convinced that this relationship is a real one. It turns out that not only do the intricately carved lions guarding decalogues (tablets with the Ten Commandments) in synagogues appear to resemble carousel horses, but sometimes the same artists made both.

Take the case of Marcus Charles Illions (1865/74-1949), a Jewish immigrant to Brooklyn from Lithuania (or Moscow; his date and place of birth are unclear). His signature appears both on several carved ark pediments (decorations above the cabinet holding the holy scrolls of the Torah), and on various carousel animals. In fact, photographs of his workshop show synagogue carvings next to denizens of the carousel.

Only recently have exhibits and books about folk arts of the world acknowledged and included Jewish art at all. Conventional wisdom holds that since the Jewish religion forbids the representation of human beings in visual art, Jewish artists have limited themselves to expressions in verbal, musical, and literary forms. That this has been so long assumed accounts for the exclusion of Jewish art from so many exhibitions. But the American Museum of Folk Art exhibit emphatically underscores that this is not necessarily the case—which is one of its numerous revelations.

Because of the crushing loss of Jewish material culture, along with millions of lives during World War II, most of the items in the show come from America. Nevertheless, collectors and scholars have succeeded in amassing an impressive array of photos and models of wooden synagogues, Torah arks, papercuts, and photos of gravestones from Eastern Europe. Of course, this can only hint at how pervasive Jewish folk art and religious art must have been once in that part of the world. Indeed, the catalog quotes the Russian modernist and avant-garde artist, El Lissitzky (1890-1941), who made a point of visiting wooden synagogues along the Dnieper River in 1916, marveling at the exquisite beauty of the carved and painted interior of the synagogue in Mogilev.

Surprisingly, although the exhibit features many different kinds of media, most of the artworks contain interrelated elements. Patterns in papercuts recall similar carved motifs in arks. The unruly manes and flashing eyes of the carved carousel horses resemble those of the lions of the ark. Gravestones, of necessity exhibited by means of photographs, also relate in iconography to synagogue decorations and papercuts.

But there is also astounding variety demonstrated. This was especially true of the myriad intricate papercuts called mizrah (meaning “east,” in reference to Jerusalem, and used as Succoth decorations), or closely related shiviti. Made primarily by men and boys, these extraordinarily elaborate papercuts were used in the home, sometimes placed in windows to celebrate holidays. Often sold by peddlers, they were also given as gifts or inserted into holy books.

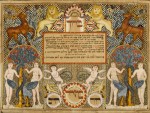

Never before have I seen a naked Adam and Eve and angels depicted by a Jewish artist. The mizrah by Tebl Prager of 1827 features not only Adam and Eve, but also the serpent, two small cherubim, and several deer and lions, all set against a highly detailed lacework background. The more than two dozen papercuts in the show were all entirely new to me, many of them belying the idea that Jewish artists refrained from depicting human beings.

Remarkably, curators of the show have managed to collect some of the original painted wooden ark carvings of lions and decorative motifs. Unfortunately most of these are American, due to European losses during World War II. A row of them are displayed across from eight carousel horses. The ferocity of many of the lions with their deeply carved manes matches the wildness of the prancing, dancing carousel horses, their manes often windblown, their mouths open, revealing prominent teeth and tongues. Jewish immigrants carved numerous horses and fantastical creatures for use in the newly emerging amusement parks of the 1920s. Many of these come from Coney Island. I remember some of them from my childhood. Indeed, the horses on the Central Park carousel (by Solomon Stein and Harry Goldstein) are still in place today.

My personal favorites are the armored horses by Stein, Goldstein, and Charles Carmel. Like many others, the Carousel Horse with Raised Headby Stein and Goldstein, made for Coney Island about 1910, has a real horsehair tail and consists of painted wood, with leather for the stirrup straps and metal for the stirrups. It prances, snorts, and neighs with its mouth wide open. If I didn’t know better, I would mistake it for one of the precious ceramic Tang Dynasty horses from China. A Jumper With Patriotic Trappings by Charles Carmel (1910, Coney Island) is amusing as it sports saddle and harness made of the American stars and stripes and an eagle.

The show is just big enough to exhibit a variety of each genre, but small enough for a viewer to take it all in and not be overwhelmed. It is a tasteful, exuberant tribute to Jewish immigrant artists and artisans.

On a personal note, I would like to dedicate this article to my late uncle, Max Joseph, who began by working in his father’s studio and then branched out for himself. Uncle Mac (as we fondly called him) made architectural decorations, some of which are still extant in the wrought iron gates for the Park Avenue Synagogue. They are unsigned, but my uncle proudly pointed them out to us whenever he visited New York City. I never before knew his ornate, scroll-like designs were part of a heritage going back many centuries to Jewish carvers of wood, stone, and metal from the old country. Indeed, they are integrally related to the ornate carvings and papercuts in this intriguing, charming, and timely show.

The American Folk Art Museum is located at 45 West 53rd Street. The exhibition runs through March 23, 2008.

Photos, from top down: Gravestone, Mszczonów, Poland, 1831 (Photo by Monika Krajewska); Top of bimah and detail of synagogue ceiling in Olkienniki, Lithuania, 18th century; Tebl Prager: Mizrah (Sukkah Decoration), Perlitz, Bavaria, 1827; Charles Carmel: Jumper with Patriotic Trappings and American Eagle, Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York, c. 1910 (Photo by August Bandal).