Column Name

Title

As a gift not only to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s longest-serving director, but also, as it turns out, to the public, curators from 17 different departments at the museum have organized a fabulous exhibition. “The Philippe de Montebello Years” honors Mr. de Montebello, who is stepping down from the directorship after 31 years, while at the same time shedding light on the entire acquisition process of a great museum.

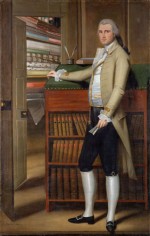

Ralph Earl, Elijah Boardman (1789), oil on canvas.

(Photo by Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)Giovanni Battista Foggini, Grand Prince Ferdinando de' Medici (c. 1676-82), marble.

(Photo by Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)Philippe de Montebello in the galleries with Andrés Segovia, on the occasion of three of Segovia’s guitars being donated to the museum in 1986.

(Photo by © Richard Lombard)Egyptian ritual figure, 4th century B.C.-early Ptolemaic period (380–246 B.C.), wood, formerly clad in lead sheet.

(Photo by Photo courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art)Body

It is hard to overstate the complexity of the challenge faced by organizers of this exhibition. The problem of how to select, arrange, and display even a small percentage of the art works acquired during Mr. de Montebellos’s tenure was daunting, to say the least. Without a chronological, cultural, or subject-oriented theme, the process of putting together such a show raised unusual questions.

The result is a knock-out … possibly even the exhibition of a lifetime! From the more than 84,000 art works the museum acquired under Mr. de Montebello’s leadership, viewers get the opportunity to visit 300 hand-chosen pieces. Helen C. Evans, curator of Byzantine art, coordinated the entire exhibition, with each department head selecting objects he or she considered transformative, and of major significance to their specialized area of art. The only organizing thread is year of acquisition. This approach enables us to garner many new insights. To see these objects in totally new surroundings and contexts is almost to see them for the first time.

The paintings, sculpture, photographs, drawings, scrolls, decorative objects, gowns, furniture, musical instruments, arms and armor are arranged as if in the elegant house of a private collector. The gracious, spacious installation allows us to appreciate these disparate works of art from many cultures and centuries as individual entities, harmonizing with one another simply because of the intrinsic beauty of each. It is truly extraordinary!

I find the entrance room to the exhibit a bit puzzling. The first object on view is the porphyry support for a Roman oblong water basin from the second century A.D. Though indisputably an important object, it does not immediately dazzle. Behind it on the wall hangs a Flemish tapestry from c. 1502-4, The Triumph of Fame. Again, it is beautiful, but does not attract one’s attention right away. In front, there is a marble bust of one of the Medici by a little-known Italian sculptor, Giovanni Foggini, and the right wall is dominated by a portrait of the back of a grotesque nude man by Lucien Freud, grandson of Sigmund. To be sure, Freud is a major contemporary painter, and there is a fascinating story behind its acquisition (listen to the audio guide on this), but it’s not clear to me why it’s there in the first room that we see.

The second room is more immediately accessible. One sees, on the facing wall, Rubens’s unforgettable, tender, sensual, colorful portrait of his young wife, Helena Fourment, and child. Next to it hangs the strikingly plain, puritanical American portrait of Elijah Boardman (1789) by Ralph Earl—in essence, the polar opposite of Rubens. In between, there are cases containing a figure from Mali, an English ivory Madonna and Child from 1300, a Greek Attic plate, and an Olmec mask, just to name a few. A Vermeer portrait and four Lorenzo Monaco small wood panels of Abraham, Noah, Moses, and David from Renaissance Italy provide a kind of counterpoint. I love the way the grid of Monacos is juxtaposed with several stark, industrial Bernd and Hilla Becher 1980 photos of water towers.

Since it is impossible to describe the wealth and variety or mention all the individual works in the exhibit, I will pick out a few of my own preferred pieces. In the third room, Luis Melendez’s Afternoon Meal (c. 1771), a paradoxically animated still life, hangs prominently, alone on the wall, between glass cases containing (at left) 52 Burgundian playing cards from 1475, and (at right) a Chinese scroll from the Northern Song Dynasty, c. 1080.

Musical instruments in the show include a 1680 viola da gamba, an Amati violin, an archlute, a rag-dung (Tibetan temple trumpet), a cittern, and one of three of Andrés Segovia’s guitars, given to the museum as a gift. The last four items mentioned are exhibited inside one case in the fourth room, but you’ll have to look for the others.

Among other favorites are the overwhelming and magnificently displayed 16th-century, six-panel Japanese screen by Sessun Shukei, Gibbons by a Mountain Stream; several Tibetan and Indonesian textiles; a Madame Grès gown (c. 1965); a large Rothko painting; an early de Kooning; an important Jasper Johns; and dozens of African, Indian, Chinese, European, and Egyptian figures.

The show could have been unwieldy in its richness, diversity, excellence, and breathtaking virtuosity. But because the organizers chose artworks that are by no means familiar icons, the overall effect is fresh and unexpected. The originality and risk-taking of placing works in new contexts pays off, resulting in a sort of museum-within-a-museum.

To supplement your pure visual delight, I would strongly recommend taking the audio tour. It tells the fascinating story behind each object, how it was chosen, acquired, and exhibited. Every object possesses its own history, and there have been as many curators, conservators, scientists, and educators involved in these processes as there are works in the exhibition.

As a consequence of my immersion in this unusual exhibition space, I experienced, upon leaving it, the curious effect of everything else becoming enhanced. All the other parts of the museum appeared much more interesting, due to my new awareness and renewed admiration for the acquisition and curatorial processes; I felt that I saw the museum through a new lens.

There are also a number of interesting events taking place in conjunction with this exhibit. See the Met’s Web site (www.metmuseum.org) for these events, as well as their unprecedented online catalogue. The exhibition continues through February 1.