Column Name

Title

I must admit hesitating before writing about Van Gogh. He needs no introduction. In fact, over the years so many students have chosen to write term papers on Starry Night that I no longer allow them to do it. All you need to do is to say the name “Van Gogh” and the crowds appear. You have to have buried your head in the sand not to know about the Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition, “Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night.”

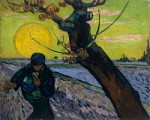

Landscape at Twilight, 1890 (oil on canvas), Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

(Photo by Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art)

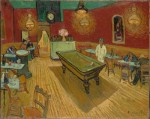

The Night Cafe, 1888 (oil on canvas), Yale University Art Gallery.

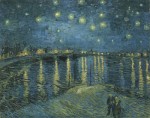

(Photo by Photo courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art)The Starry Night Over the Rhone, 1888 (oil on canvas), Musee d'Orsay, Paris.

(Photo by Copyright Reunion des Musees Nationauz/Art Resource, NY. Photo Herve Lewandowski)Body

However, not to focus on this, the most moving exhibition in New York, would be irresponsible. And it just might be illuminating at this point to ask why so many are drawn to this ill-fated Dutch artist’s works. Maybe it’s because he punches us in the gut immediately, but then calls us back to look over and over again at his painting, constantly finding something new.

The Museum of Modern Art has done a clever thing by not having yet another blockbuster Van Gogh retrospective, and instead limiting this show to just one aspect of the master’s work: paintings about nighttime.

The exquisite show is small: just 23 paintings and 10 works on paper. There is no sales gallery at the end of the exhibit with Van Gogh cups, scarves, and the like. It is one of those rare shows nowadays—of a major artist, simply focusing on his art.

Interestingly, the exhibition begins with several amateurish paintings and drawings, demonstrating the artist’s early inexperience and lack of training. But then it goes on to show how rapidly he learned. This is particularly fascinating in the first room, where, right next to a clumsy 1883 Twilight, Old Farmhouses in Loosduinen there hangs a highly achieved painting done just two years later, and on the back wall is the transcendent 1890 Landscape at Twilight from the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam. We realize with a start that Vincent’s entire oeuvre is contained within a 10-year period, and mostly within the five years from his 1885 The Potato Eaters to his Crows Over the Wheatfield (not in the show), the field where he shot himself in 1890.

In these few small galleries you will find mostly unfamiliar works, but along with them are some of the greatest paintings: Potato Eaters, two versions of The Sower, The Night Café, Starry Sky Over the Rhone, and MoMA’s own, iconic Starry Night.

If you allow yourself, you can look at these paintings in a new way. I would ask why Vincent felt such attraction to the night, and how he saw so much color and such a multitude of reflections during a time when there was no electricity, and only gas lights?

There can be no question that Vincent was a visionary; to take him at his word as a painter of everyday reality and observable fact is surely insufficient. For me, Starry Night Over the Rhone (Musée d’Orsay) of 1888 was a revelation. Perhaps because we are so used to our own Starry Night, the explosion of this painting out of the darkness comes as a shock. The stars jump out of the sky twinkling each with its own vitality, as the much-too-bright reflections of gas lights contrast with the dark blacks and blues of water and sky. The wall label refers to the couple in the lower-right corner as romantic and amorous, but I find them tiny, perhaps frightened, and certainly alone—small blobs of paint, stranded among the undulating brushstrokes that frenetically jump between foreground, midground, and background. Two ominous, inexplicable bumps loom above them at land’s end. Are they grave sites?

The night could be for Vincent a positive time—one in which he portrays farmers sowing seeds, germinating new life; a time for dreaming and inspiration, as well as pondering vastness and creativity. It was evening when the impoverished peasants sat down to their meager meal in The Potato Eaters; there, the lone lantern pierces the blackness like a large eye, shedding light on the hands and faces of the dingy, dust-covered family. Incredibly, small glints of pinks, reds, yellows, and greens enliven hands, fingers, strands of hair, and parts of faces. With minimal light and the use of a few gestures, the painter suffuses the canvas with love amidst poverty and simplicity.

At the same time, the night could be filled with terror, as The Night Café of 1888 illustrates, with its isolated figures hunched over blue-green-topped tables. The café is the converse side of the external, starry night. Instead of a dusky background enlivened with blazes of color, a grotesque artificial yellow light vibrates out from the now threatening-looking, eye-like lamps. A lone figure in white stands awkwardly near the pool table, and the steep perspective emphasizes the ugly shadow it casts, as well as the bizarre, ghost-shaped opening in the door, leading to where? A black clock stops time ominously at about a quarter past midnight. Vincent well knew that this was a nightmare vision, and wrote about it at length. He described the complementary colors and their infinite subtleties in excruciating detail, ending with the famous quote that this was a place where “you can ruin yourself, go mad, commit crimes.”

Van Gogh wrote extensively about his work and his ideas. We know that he was acutely aware of every line, dot, dash, and color he chose to use. He spoke and wrote in four different languages. It is not accidental that no one can resist being pulled inside his canvases. But it is beyond irony to think that this incredible genius was driven to suicide, to the very madness he so feared, at least in part due to lack of recognition in his own time.

Vincent Van Gogh, now long departed into his own dark night, must be wondering what madness causes people to pay hundreds of millions of dollars for paintings he could not even give away during his lifetime. I cannot even imagine, as I walk among his varying depictions of dream, nightmare, love, and life, what he would have thought of this strange turn of fate.

Although there is no extra fee, timed entry tickets must be obtained to go into the exhibition. I recommend coming when the museum opens, if at all possible. “Van Gogh and the Colors of the Night” runs through January 5; the Museum of Modern Art is located at 11 West 53rd Street.