Title

This year’s Focus! festival enters uncharted waters with the inclusion of John Adams’s 1991 opera, The Death of Klinghoffer, as the final event on January 31. Presented in a semistaged version by the Juilliard Opera Center, conducted by the composer and directed by Ed Berkeley, the production marks the first time in the festival’s history that a full-length opera has been featured.

Body

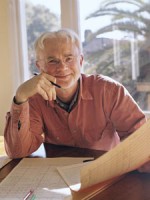

As for its connection to the festival’s California theme, Adams, 61, has been one of the leading figures on the West Coast contemporary music scene ever since he moved from his native Massachusetts to San Francisco in 1971, at the age of 24. A faculty member at the San Francisco Conservatory from ’72 to ’82, Adams became the new-music advisor to the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1978 and served as its composer-in-residence from ’82 to ’85.

Like his earlier opera Nixon in China, The Death of Klinghoffer is based on actual events—namely, the 1985 hijacking of the Achille Lauro, an Italian cruise ship, by four members of the Palestinian Liberation Front. Bargaining by radio for the release of 50 Palestinians held in Israeli prisons, the terrorists held everyone aboard the ship as hostages and, during the course of their negotiations, murdered a wheelchair-bound Jewish-American passenger, Leon Klinghoffer. (The hijackers were ultimately captured and jailed.) In addition to the four terrorists and Mr. Klinghoffer, the opera portrays Marilyn Klinghoffer, the victim’s wife; the ship’s captain; and several fictionalized, generically named passengers (e.g., the “Swiss Grandmother”).

Unfolding over two acts with two scenes each, The Death of Klinghoffer is more of an opera-oratorio hybrid than a traditional opera, utilizing choruses as well as soloists to tell the story. Commenting on the sense of historical perspective he hoped to invoke, Adams notes (in Michael Steinberg’s liner notes for the 1992 Nonesuch recording of the opera) that “you have a constantly shifting scale of closeness and distance … At one moment you feel as though you’re right there on the deck under the blistering sun with the rest of the passengers, and a moment later you feel like you’re reading about it in some very ancient text.” Alice Goodman’s libretto, written entirely in couplets, enhances the “archaic” effect of such moments. The dramatic structure also departs from convention in the general lack of interaction between the characters, who spend much of their time, especially in Act I, revealing their interpretation of events and motivations directly to the audience.

Co-commissioned by the San Francisco Opera, Los Angeles Opera, Brooklyn Academy of Music, Glyndebourne Festival, and La Monnaie, The Death of Klinghoffer was premiered on March 19, 1991, at the Théâtre Royale de la Monnaie in Brussels. The production was directed by Peter Sellars and conducted by Kent Nagano, with choreography by Mark Morris.

To say the opera generated controversy is an understatement. A review of the Brussels premiere by Manuela Hoelterhoff in The Wall Street Journal said the opera “turns the sport-killing of a frail old Jew in a wheelchair into a cool meditation on meaning and myth, life and death.” When it came to BAM in November 1991, many critics, including Edward Rothstein of The New York Times, felt the terrorists were too sympathetic, and the treatment of Israelis versus Palestinians biased towards the latter. The Times also published a statement by Mr. Klinghoffer’s daughters, Ilsa and Lisa Klinghoffer, who had attended the opera anonymously and felt that the opera exploited their parents, “appeared … to be anti-Semitic,” and was “historically naïve.” Both Adams and Goodman, who identified herself as Jewish (but later converted to Christianity), strongly denied any such intentions.

Although the production travelled to San Francisco in 1992 as planned, in the wake of the controversy, both Glyndebourne and Los Angeles refused to stage it. With opera houses declining to mount further productions of the work, the controversy eventually faded, but was reignited in November 2001 when the Boston Symphony Orchestra dropped excerpts from the opera from a scheduled program in light of sensitivities following the September 11 attacks. Adams disagreed with the decision on principal. In an interview with Elena Park for the Web site andante.com, he stated that “people in the art world or the theater world, people who read novels and go to see provocative new films expect to be challenged, and even on occasion to be upset. But classical music consumers are being typecast as the most timid and emotionally fragile of all audiences.”

The esteemed musicologist Richard Taruskin, author of the epic six-volume Oxford History of Western Music, disagreed. On December 9, 2001, The New York Times published a lengthy article by Taruskin titled “Music’s Dangers and the Case for Control.” Arguing that the opera does indeed “romanticize the perpetrators of deadly violence toward the innocent,” Taruskin concludes that “Censorship is always deplorable, but the exercise of forbearance can be noble. Not to be able to distinguish the noble from the deplorable is morally obtuse … Art is not blameless. Art can inflict harm.” Despite Taruskin’s enormous influence, Adams gained many defenders with his response that, “Not long ago our attorney general, John Ashcroft, said that anyone who questioned his policies on civil rights after September 11 was aiding terrorists; what Taruskin said was the aesthetic version of that.”

Adams and Taruskin may never have mended fences, but audience and critical reception to subsequent productions, most notably at BAM in 2003 and the Edinburgh Festival in 2005, have been generally positive, and a film version of the opera by Penny Woolcock, released in 2003, was especially well received. Mark Swed of The Los Angeles Times has described Klinghoffer as “one of the most beautiful operas written in my lifetime.”